James Christopher Timbrell (1807-1850): Carolan, the Irish Bard, 1844

The O'Brien Collection

The Painting

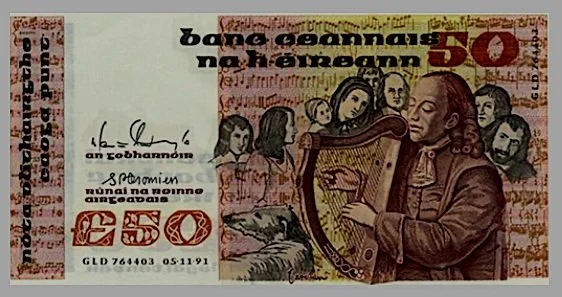

The story of the painting’s disappearance from Ireland, its long sojourn in Stockholm, Sweden, and return again over a century later is an interesting one. Much like the painter himself, who virtually disappeared from historical records after this painting was exhibited in 1844, there is little knowledge of the specific where- abouts of the painting between 1844 and 1948. It was believed to have been in the possession of a Swedish nobleman until it was acquired in 1948 by a café owner in Stockholm from a local antique dealer. It hung on the wall of his café until the mid-1970s when, by virtue of the keen eye of the Reverend Joseph Maguire, a cleric from Downpatrick, County Down, it was purchased and brought to Ireland. The priest’s correspondence with the Irish Ambassador to Sweden—for the purpose of researching the provenance of the piece—yielded some important facts about the painting’s history; it also resulted in the painting being depicted on the Series B banknotes being designed at the time, which featured important historical themes and persons. The scene illustrated here was represented on the verso of the Series B fifty-pound note, which remained in circulation from 1977 until 1992, when it was replaced by the final Series C banknotes, which stayed in circulation until the advent of the Euro currency in 2002. (Marty Fahey)

The Painter

James Christopher Timbrell (1807-1850)

From A Dictionary of Irish Artists, 1913

Was born in Dublin in 1807, the younger brother of Henry Timbrell (q.v.). In 1825 he entered the Royal Dublin Society's Schools, and in 1827 sent a View on Howth Road, near Kilbarrack to the Royal Hibernian Academy, his first and only exhibit. He presented to the Dublin Society, in 1829, a lithograph, The Scotch Fisher, done by him. In 1830 he went to London and sent a portrait to the Society of British Artists, and a picture, Summer, to the British institution, which were followed by other works in 1835, 1836 and 1842. He made his first appearance at the Academy in 1842 with his Returning from Market; in 1844 he exhibited a Portrait of Carolan, the Irish Bard, and in 1848 a "bas-relief, part of a monument to be erected in marble." He contributed eight illustrations to Hall's Ireland, its Scenery and Character. He died at Portsmouth, after a painful illness, on the 5th January, 1850.

The Story

1844 catalog entry for Royal Academy exhibition in London

The painting depicts a popular though apocryphal story, first recorded by Oliver Goldsmith in 1760, of a meeting between Carolan and the famed Italian musician, composer, and theorist Francesco Geminiani (1687–1762). W. H. Grattan Flood relates the story in A History of Irish Music (1905):

At the house of an Irish nobleman, where Geminiani was present, Carolan challenged that eminent composer to a trial of skill. The musician played over on his violin the fifth concerto of Vivaldi. It was instantly repeated by Carolan on his harp, although he had never heard it before. The surprise of the company was increased when he asserted that he would compose a concerto himself at the moment, and the more so when he actually played that admirable piece known ever since as Carolan’s Concerto.

This painting depicts the meeting between Carolan and Geminiani as taking place Castle Bourke, then the seat of Theobald Bourke, the sixth Viscount Mayo. The castle is located about 5 miles from Castlebar, down the road from Ballintubber Abbey (the burial place of the Bourkes.) The castle apparently came into the family via the second Viscount's foster father, Miles MacEvilly, and was formerly known as Kilboynell.

While some lands were lost between the time of the 2nd Viscount and the 6th, the castle was in the family's possession during the time of the 6th Viscount, having been returned as part of a land grant given to the 4th Viscount Mayo upon the restoration of Charles II. While there is some suggestion that it may have been sold by the 5th Viscount to his father-in-law, Col. John Browne, given that Castle Bourke formed part of the inheritance of the grandson of the 8th and last Viscount, it must certainly have returned to the possession of the Bourke family, presumably via inheritance from the Browne side of the family, if indeed it ever in fact left their control. In any case, it is reasonable to assume that Castle Bourke belonged to the 6th Viscount in Carolan’s time.

For more on Geminiani’s time in Ireland, please see the first section of this paper by Rudolf Rasch.

Carolan and the Bourkes

A Bourke civil war in the 1330s ended with the loss of lands in Ulster, and confirmed the continuing existence of separate, rival branches of the family in political opposition to each other. The Viscounts of Mayo were descended from the Mac William Íochtar branch of Bourkes, also known as the Mayo Bourkes. They were descended from William de Burgh's oldest son and heir, Richard Mór de Burgh.

The noble Bourke branch to whom Carolan can be most closely tied are the Baronets of Glinsk, descended from the youngest son of the youngest (illegitimate) son of William de Burgh, founder of the dynasty. As a minor branch of the family, also known as the MacDavid Bourkes, they were not nearly as powerful as the descendants of the illegitimate Richard Óg's second son, who became the Earls of Clanricarde, patrons of the Connellan harpers. Their seat was Glinsk Castle in Galway.

The other Bourke branch known to have patronized Carolan was not noble, but was also strongly Jacobite. The main member of this family was Thomas Bourke, Esq, MP for Castlebar in the Patriot Parliament of 1689. He was descended from the Mac William Burkes and was closely related to the Viscounts Mayo, but his ancestor Richard MacWilliam Bourke resigned his lordship around 1469 to found the Burrishoole friary. Subsequently the line of succession passed through Richard MacWilliam Burke's nephew.

This succession ended in 1602 with the 21st MacWilliam Íochtar chieftain, who famously fought his rival Tibbot na Long Bourke, the illegitimate son of “pirate queen” Grace O’Malley and the 18th MacWilliam Íochtar. Tibbot na Long Bourke won the dynastic war and acquiesced to the policy of surrender and regrant, after which he was created the first Viscount Mayo. He acquired Castle Bourke, then known as Kilboynell, in 1611, from his foster-father, a MacEvilly.

It is worth noting that Carolan's known Bourke connections are with branches of the family that generally opposed the Viscounts Mayo, for both dynastic and ideological reasons. There are a few assertions that our Lord Mayo was an "important patron" of Carolan, but none are well-sourced. The claim seems to originate with Grattan Flood, who is also the source of the claim that a tune attributed to Carolan by O'Neill, known as "Peggy Browne" or "Planxty Miss Browne," was written for a Margaret Browne, who was supposed to have married the 6th Viscount Mayo in 1702. However, primary sources show that the 6th Viscount’s first wife was his cousin Mary/Maud Browne, not a Margaret Browne. Donal O'Sullivan does not believe the title is correct, nor that the tune can be definitively linked to Carolan, though he allows that it is possible, based on compositional style.

The Research and The Tune

Research on this painting, and the scene depicted in it, has been an ongoing collaborative project between art curator and musician Marty Fahey of The O’Brien Collection and harper and researcher Marta Cook, both based in Chicago. More of our research will be shared here over time - watch this space!

To commemorate this ongoing work, Marty composed "Marta's Musings,” a beautiful jig by Marty. It appears in his 2022 collection of original tunes, The Dreamer. Marty notes:

As this tune started to emerge, I had two reactions to it: 1) that it had an understated lyricism/ happiness about it and 2) that I imagined the resonance of harp playing as a way to showcase it the best. Having arrived at those conclusions, it was only natural to dedicate it to Marta who had, over the past couple of years, helped me with a couple of musical videos and was also my "fellow detective" in getting to the bottom of a mystery that prevailed on one of the more important "harping" paintings in the canon of Irish art, James Christopher Timbrell's, Carolan, The Irish Bard, c 1843-1844. Though the rediscovery of the painting (in a cafe in Stockholm in the early 1980s) led to its use as the Series B Irish 50 pound banknote, a further mystery prevailed: where did this alleged musical duel between Carolan and Francesco Geminiani take place? Months of emails and conversations about these related subjects with Marta pointed the direction to the eventual name of this tune, "Marta's Musings."

In honor of Lá na Cruite | Harp Day, Marta arranged the tune for solo harp and created a music video featuring images of and associated with the painting, including the banknote and the ruins of Castle Bourke on shore of Lough Carra, which dissolves into the Chicago skyline on the shore of Lake Michigan - evoking both the emigrant's journey, and the continuity of the harp tradition across time and space.

Interpretation of the Painting

Viewers of this piece in 1844 would have recognized the obvious and less obvious clues with a facility for 'decoding' history paintings that modern audiences have lost sight of in the last century and a half. (The camera all but replaced the lofty status of history painting as a genre.)

The painting is full of symbolism and reference that would have been intelligible to informed viewers. For example, the armor hanging on the wall is a symbol of the family’s military background. The "Elk" horns (actually a giant Irish deer) are a symbol, in the present as well as the past, of the longevity of the landed gentry's claims to their property. We can also observe the compositional influence of Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

We can also observe notable figures in the painting. While these identifications are not definitively proven, they are intriguing possibilities. For example, the figure meant to represent Geminiani appears behind Carolan, as an observer, not an actor; the dark-haired gentlemen in the center of the composition is likely to represent the Sixth Viscount, Theobald Bourke.

Geminiani?

Conclusions

The story of Carolan and Geminiani is depicted in this painting not because we know that it happened - that is impossible to know - but because it is a compelling narrative about power, in which “native” Irish musicianship is able to win out over Italian cosmopolitanism when “Carolan, the Irish Bard,” proves capable of besting the “foreign master” at his own game.

Professor Barra Boydell, the esteemed musicologist and Senior Lecturer in Music at Maynooth, gave a brilliant lecture on Geminiani’s time in Ireland, including the story of the encounter with Carolan. Prof. Boydell’s interest lies in the ways that the figure of Geminiani, for decades after his death, was used as a foil to bolster nationalist concepts regarding music as central to establishing the existence of an "ancient Irish people" deserving of their rights as a people. He argues that the Carolan/Geminiani story may be a cornerstone of a larger mythology in support of a political ideology - which could certainly help explain why Timbrell may have chosen this encounter as his subject, and why the painting is so rich with symbolism that creates a narrative of power.

What does any of this have to do with harpers now?

Well, that’s a matter of personal opinion, but perhaps it is relevant to us to understand that there is a misleading dichotomy opposing “folk" to "fashion" with regard to the harp tradition.

We know there are intimate links between the harp tradition and baroque music going back at least a century before Carolan, in addition to the huge popularity of Italian music among harpers in the 18th century specifically. That is well-documented, from Cornelius Lyons’ baroque-style variations, performed and greatly admired by Donnchadh Ó hAmhsaigh, to Echlin Kane, a student of Lyons, who was said to have learned Correlli concerti accurately, presumably by ear, and performed them magnificently.

In the early seventeenth century, there is compelling evidence to suggest not only that English composer William Lawes composed his Harp Consorts for the wire-string Gaelic harp, but also that his consorts were not the first of their kind and that in fact theIrish harp was used in consort with a variety of instruments in English and European courts. Pictorial evidence survives in the form of a painting of a consort (with different instrumentation than that of Lawes) including an Irish harp at the Danish court (Reinhold Timm, 1639.) Additionally, fragments of consort parts written by Irish harper Cormacke McDermott survive (though not harp parts.)

It’s quite odd historically to paint Irish harpers in general as strangers to European art music prior to the arrival of Italian musicians in Dublin in the eighteenth century. The evidence overwhelmingly suggests that generations of harpers were professionally conversant with multiple styles of music, and that far from being an anomaly, this was more or less de rigeur. Rather than isolated, exotic specimens representing an imaginary, romanticized "Gaelic purity," Irish harpers could and regularly did employ a wide variety of skills in multiple genres, and this in no way diminished their skill or stature as traditional musicians. This seems to have held trueof Irish harpers both blind and sighted, fully professionally trained or comparatively amateur, until political and economic upheaval (and particularly the Penal Laws) affected the ability of musicians to seek both training and employment.

By the late eighteenth century, the harp tradition in general had obviously declined so dramatically that none of this was immediately obvious to most interested parties. Indeed, it was not a sufficient lack of “Gaelic purity,” to reference Flann O’Brien, that diminished social status; rather, it was the social and economic impacts of colonial dispossession on their material well-being.

The Music

In honor of Lá na Cruite | Harp Day 2023, here is a free download of Marty’s tune, as played by Marta in the above video, arranged for intermediate-advanced solo harp. Enjoy, and Happy Harp Day!